Diving Deep: FC Tulsa 1-3 Birmingham LegionPossession? We don't need no stinking possession

The Legion has won two straight games by not holding on to the ball in any significant way. This was moderately the case against Louisville City, in which the Three Sparks had a small possession disadvantage of just 0.2%. In Tulsa though they took it to extremes. The team ended the game with a meager 30.7% of the possession, and in fact only broke the 30% mark late in the game when they were holding on to the ball and basically seeing the game out.

They attempted just 263 passes to Tulsa’s whopping 607. No one on the team had more than 33. Absurdly small, especially given the final scoreline. In virtually every statistic Tulsa had the upper hand.

Except, of course, they really didn’t.

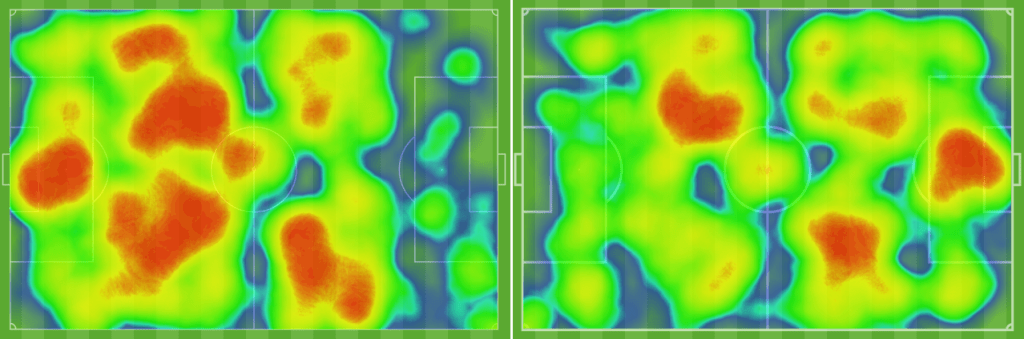

The Louisville and Tulsa games were alike in that the counterattack was the main strategy. They were unalike in other ways, though. Against Lou City the Legion was content to sit back and absorb pressure. Against Tulsa they used more of a high press to keep Tulsa in their own end. The heatmaps for the two games show this:

These are both the Legion only, not both teams. The Lou City game is on the left, Tulsa on the right, the Legion playing towards the center of the graphic in both cases. The Louisville game shows much more red because of the heavy concentration of possession in the one end. Not to mention the limited incursion into the Lou City penalty area. The Tulsa game is far more distributed and has considerably more possession dep in the Tulsa end and box. This also explains how the Legion managed 11 shots against Tulsa with 30% possession as compared with just 8 shots on 50% possession at the weekend.

Tommy Soehn was, I suppose, forced into a a strategic decision on Wednesday by the suspension of Alex Crognale. He was short a starting centerback, which basically meant Jake Rufe had to start. That in turn meant Jake was not available as a bench option in any number of position as he had been on Saturday. On both occasions the team was in a nominal 4-2-3-1. As we have already seen, against Lou City that morphed into an effective 3-man back line with Moses Mensah hanging deep and freeing Collin Smith to roam forward. Enzo Martinez was in the double pivot with Matthew Corcoran, a remarkable piece of fakery that completely fooled Louisville. The formation was, to all intents and purposes, a 3-1-4-2, a slightly more defensive version of the 3-5-2.

The team was announced as a 4-2-3-1 against Tulsa as well, but with a different lineup. Jake was in for Alex, and Prosper was in the double pivot. Supposedly. Here are the average positions for the game:

There are any number of ways you could break this down. Yet again, Collin (#4) was higher than Moses (#33), but not so much that a 4-man back line isn’t in operation. Oddly, it was Moses getting caught a tad too high that led to the Tulsa goal. The double pivot, marked with the tightly-spaced dots is also evident. But Prosper (#10) is, like Collin, in a much higher position than Matthew (#17). This is normal for a double pivot, but when you have a natural attacking player like Prosper or Enzo in that higher slot it may as well not exist at all. Which is why I have included a dotted line attaching Prosper to the attacking mids. That is, this was effectively a 4-1-4-1. You might also argue that this was a 3-3-3-1, but that is normally used for ball possession. It does however take advantage of large numbers of midfielders, which the Legion has in spades (remember that Collin is at least as good as a wingback as he is as a fullback).

Now let’s compare that to how the Legion averaged against Louisville:

Other than being more compressed and withdrawn and taking into account swapping Jake for Alex and flipping the roles of Enzo and Prosper, the only real difference here is that Neco Brett (#11) is in a much deeper role than in Tulsa. Given his scoring in the 2 games, hardly surprising. In both games we saw a fullback playing more as a winger (Collin) and a nominally defensive mid (Prosper or Enzo) playing a more attacking role, but never in such a way as not to be able to return easily to defensive duties. Enzo had 18 defensive actions against Louisville and Prosper 12 against Tulsa.

Note that these are the starters only; with some of the substitutions the tactics changed, especially late when the Legion was up 2 goals in each instance and basically killing off the clock. Which it did in both cases by attacking as much as by defending.

The points I am trying to get across here are these: first, that almost any formation can be very fluid. But more importantly, second, that this formational fluidity is in turn dependent on the positional flexibility of the players on the team.

Yes, that’s right, we’re back to Total Football once again. And that’s not just because I grew up watching the brilliant Dutch teams of the 1970s (yeah, I’m that old). Rather, it’s a beautiful way to play the beautiful game. And the Legion is built in a lot of ways for this very purpose. Or at least, it appears to be. Whether that’s by design or by chance, Coach Tommy Soehn has certainly glommed onto it.

This blogger and several others have posted on XTSMAFKAT1X, the social media app formerly known as Twitter jokingly noting the preponderance of wingers on the Legion roster, Tyler Freeman and Tabort Etaka Preston being the latest such additions. Well, yes, that is true, but if the players on the roster are capable of playing multiple roles it is not a problem. Enzo for one can play pretty much anywhere he wants to. Prosper over the past two weeks has excelled in a more central role than we are used to seeing him in. Juan Agudelo is thriving as a holdup attacking mid. Tyler Pasher loves to bring the ball inside, so he can likely do that too (he’s still a few weeks from returning apparently) and Anderson Asiedu is a multipurpose central midfielder (again, when he’s fit). We even have a fullback in Jake who can also play centerback and winger as required.

So, what looks like a perplexing problem is in fact a champagne problem. Or perhaps, in light of the team’s primary sponsor, a Coca-Cola problem.